|

|

The Middle Passage:

Slaves at Sea

The "Middle Passage" was the journey of slave trading ships from the west coast of Africa, where the slaves

were obtained, across the Atlantic, where they were sold or, in some cases, traded for goods such as molasses, which was used

in the making of rum. However, this voyage has come to be remembered for much more than simply the transport and sale of slaves.

The Middle Passage was the longest, hardest, most dangerous, and also most horrific part of the journey of the slave ships.

With extremely tightly packed loads of human cargo that stank and carried both infectious disease and death, the ships would

travel east to west across the Atlantic on a miserable voyage lasting at least five weeks, and sometimes as long as three

months. Although incredibly profitable for both its participants and their investing backers, the terrible Middle Passage

has come to represent the ultimate in human misery and suffering. The abominable and inhuman conditions which the Africans

were faced with on their voyage clearly display the great evil of the slave trade.

To learn more about the transatlantic slave trade, click below:

- Spain vs. England: The Early History of the Slave Trade

- The Bottom of the Triangle: The Economic Role of the Middle Passage

- Hell Below Deck: Life on the Slave Ships

- Brutal Voyage: The Daily Routine on the Slave Ships

- Fighting Back: Revolt on the Slave Ships

- The Toll of the Trip: Death on the Slave Ships

- A Great Sin of Humanity: The Legacy of the Middle Passage

|

Celebrating Black History Month 2006 Celebrating Black History Month 2006

The Black West

"If the American

frontier did not exist, it would have to have been invented." —Voltaire

"The frontier is the most American part of America." —Lord Bryce

"The Westerner has been the type and master of our American life." —Woodrow Wilson

In the nineteenth century scholars transformed our frontier saga from a grim duel with nature that unleashed the worst

and best in people into a national mythology to honor Europeans for building a nation in the wilderness. This revised tale

was not subject to Indian claims. It forever omitted people of African descent, and denied them a place in dime novels, school

texts and tales of pioneer life. When 20th Hollywood's central casting selected actors to race across silver screens, African

Americans were invisible.

This has begun to change. Like the dark, mysterious figures in "horse operas" that suddenly ride into town only to be recognized

as missing earlier settlers, African American men and women of the West have come home. Scholarly diligence has cleared a

path for these long neglected pioneers to enter the public consciousness.

From the dawn of the earliest foreign landings Africans were a crucial force in the New World. Professor van Van Sertima

has documented their presence before Columbus thought of sailing westward to reach the riches of Asia. Their presence after

Columbus has been affirmed in explorers' diaries, viceroys' letters, church records, government reports, fur company ledgers,

recollections of Indians and whites, newspaper accounts, and census reports. Their faces have been captured in sketches by

artists Charles Russell and Frederick Remington, and by early professional and amateur cameramen, military and civilian. Some

sat for portraits in pencil or oil and others kept diaries, notes or wrote letters. These tell of Black families that forded

rivers, scaled mountains, and slogged through marshes and deserts, and on the way enriched the culture and economy of America's

frontier. The frontier role of African Americans—often buried, strayed or lost from view—is now clear.

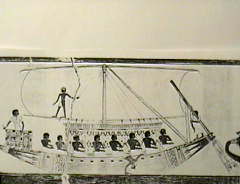

Pietro Alonzo il Negro, traveling with Columbus in 1492 was pilot of the Nini. In 1513 African laborers marched

with Vasco Balboa when he stumbled on a village of African people near Panama whose existence has never been fully explained.

Other Africans marched into the wilderness alongside of, or a little ahead of Father Serra, Chief Pontiac, Ponce de Leon and

Davy Crockett. Slaves, fugitive slaves, or free, they entered the continent as explorers, fur trappers, adventurers, school

teachers, homesteaders, deputy sheriffs, cowboys, soldiers, outlaws, miners, journalists and entrepreneurs.

Europeans first built their American labor system on Native American enslavement, and soon began to feed in captured Africans.

Two peoples of color became husbands, wives, sisters and brothers, and with Native Americans showing the way, together they

fled their chains. In 1503 when Governor Ovando of Hispaniola reported his African slaves fled to the rainforest, his complaint

that they “never could be captured” probably meant they had found a red hand of friendship. Africans were welcomed

by an Indian adoption system that drew no color lines. They also arrived with unique agricultural skills and a familiarity

with European weapons and diplomacy.

In a grim record filled with ironies, the subjugation of the New World was led by Spain, since 711 when Moors invaded the

Iberian Peninsula, a nation of mixed races. The opening of Africa by European merchants in 1442 and Spain's expulsion of the

Moors in 1492 enabled the invaders to make the New World a massive experiment in colonization and enslavement.

Africans, slave and free, traveled as soldiers or laborers with each European expedition to the Americas. They landed in

Florida with Ponce de Leon and in 1519 Africans dragged the cannons Hernando Cortez used to vanquish the Aztec empire. Others

marched under the Pizarro brothers in their conquest of Peru and still others aided Francisco de Montejo to subdue Honduras.

In 1539 Estevanico, an African Moor who easily picked up Indian languages, served as the scout for an exploration led by Farther

Marcos de Nizza. Estevanico, accompanied by 300 Indians, became the first non-Indian to enter Arizona and New Mexico.

Though colonial officials warned about the danger of Africans associating with Native Americans, European armies

of occupation invariably included men of African descent. Many took the opportunity to flee to Indian villages beyond the

European bastions that dotted the coastlines. A European report from Mexico in 1537 noted: "The Indians and the Negroes daily

wait, hoping to put into practice their freedom from the domination and servitude in which Spaniards keep them." That year

Black miners in Amatepeque, Mexico revolted, elected a ruler, and assisted by Native Mexicans, militarily challenged Spanish

hegemony.

In 1579 four Africans accompanied Sir Francis Drake when he landed in San Francisco. In 1588 Africans helped Juan de Onate

colonize New Mexico and remained to take part in its civil wars two generations later. They joined and helped lead the Pueblo

Indian uprising of 1680 that overthrew Spanish rule. Beginning in 1769 Africans helped Father Junipero Serra's Jesuit missionaries

build missions in California. Those who remained appear in church birth, marriage and death records, and others melted into

Native villages.

From the North Carolina's Great Dismal Swamp to Brazilian rainforests two peoples of color fled together and formed "maroon

societies." Though most maroon communities were committed to trade and/or agriculture, Europeans considered them bandits and

one scholar called them "the gangrene of colonial society." Europeans conducted unrelenting legal and military assaults on

their right to survive as alternative societies. By the American Revolution hundreds of armed Africans and Seminoles had settled

along Florida's Apalachicola River. The Africans taught arriving Seminoles, a breakaway segment of the Creek nation, methods

of rice cultivation they had learned in Senegambia and Sierra Leone. On this basis these red and black people formed an agricultural

and military alliance that held the United States Army, Navy and Marines at bay for forty-two years. The New World's first

written protest was a declaration signed in 1600 by Isabel de Olivera before she accompanied Juan Guerra de Resa's expedition

to New Mexico. Born of an African father and Indian mother, Olivera said she had "some reason to fear I may be annoyed [because

of race]." She wrote: "I demand justice."

In 1781 Los Angeles was founded by 46 people (11 different families) and 26 were of African descent. One, Manuel Camero,

served on the city council from 1781 to 1816. Another, Francisco Reyes, owned the San Fernando Valley and until he sold it

and became the city's first mayor. Maria Rita Valdez, daughter of a Black founder, owned Beverly Hills, and still others owned

large tracts of land and large herds of cattle. In 1790 a Spanish census of California uncovered a sizable African presence:

San Francisco, 18%, San Jose, 24%, Santa Barbara 20%, Monterey, 18%.

Texas also had a richly diverse population. San Antonio was founded in 1718 by 72 people, many of African descent, and

in 1777 151 Africans were listed among its 2,060 residents. In 1789 of Laredo's 708 residents 119 were of African parentage.

However, after 1795 when Spain's King Charles III declared Africans inferior to Spaniards, and the Crown sold certificates

allowing residents to claim greater Spanish blood, the census reported a sharp drop in the number of Black people.

In the 1820s enslaved men and women, free people of color and runaways, some responding to Stephen Austin's invitation,

entered east Texas from the United States. Fugitive slaves and others sought the liberty promised by anti-slavery Mexican

officials. In 1829 Vicente Guerrero, a revolutionary hero born of African and Indian parents, became president of Mexico,

wrote its new constitution and liberated its slaves.

By the 1830s free African Americans in Texas had made their mark. In the southeast the four Ashworth brothers owned almost

two thousand acres of land and 2,500 cattle, and were able to avoid military service by hiring substitutes. In 1831 Greenbury

Logan traveled to Texas with Stephen Austin where he volunteered for and was severely wounded in the war that freed Texas

from Mexico. The slaveholders who came to rule the Lone Star Republic showed no respect for the rights of this wounded Black

veteran. During the Mexican War Texas' slaves fled plantations to the Colorado, the Nueces and the Red Rivers, or to Commanches

or Santa Ana's armies. Pio Pico, born to a prominent family of mixed African descent, was the last Mexican governor of California.

He served from 1845 to 1846 when he surrendered to the victorious U.S. army.

In San Francisco, William Leidesdorff of Danish-African de-scent, a wealthy and fervent U.S. partisan, in 1845 was appointed

a U.S. vice-consul by President Polk. He secretly plotted to overthrow Mexican rule and not only welcomed U.S. Captain John

Montgomery and his army, but spent a night translating the proclamation on the transfer of power that Montgomery read to the

assembled citizens at the plaza the next day. |

Celebrating Black History Month 2006 Celebrating Black History Month 2006

The Black West

The American Revolution

led to settlement of the Ohio and Mississippi valley. Some Black people arrived as missionaries, others as trappers, schoolteachers,

adventurers and runaways. In 1779 Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable built a trading post near a lake in the Illinois territory,

married a Potawatomie woman, made friends with Chief Pontiac and Daniel Boone, and his settlement grew into the city of Chicago.

Colonel James Stevenson, who lived for 30 years among Native Americans, in 1888 wrote: "The old fur trappers always got a

Negro if possible to negotiate for them with the Indians, because of their 'pacifying effect.' They could manage them better

than white men, with less friction."

James P. Beckwourth, a handy man with a Bowie knife, gun or hatchet, cut a jagged path from St. Louis to California and

back to Florida as a fur trader, army scout and warrior-for-hire. In April 1850 he discovered a pass in the Sierra Nevadas

important to the California 49'ers, and Beckwourth pass, a nearby town and a peak still bear his name. In the age of Daniel

Boone, Jim Bowie and Davy Crockett, a western writer called Beckwourth "the most famous Indian fighter of this generation."

Thousands of slave runaways lived among the Six Nations of the northeast or the Five Civilized Nations of the southeast.

Frontier artist George Catlin described their offspring as “the finest looking people I have ever seen.” When

the U.S. government forced 14,000 Cherokees into a mid-winter "Trail of Tears" march from Georgia to Oklahoma the Cherokees

had 1,600 African members.

During the Gold Rush upwards of two thousand African Americans flocked to California and one thousand called themselves

prospectors. Some were free, and some of the enslaved were sent or taken by their gold-seeking masters. A few Black men gathered

enough gold nuggets and dust to purchase their freedom. In cities some African Americans became chefs, entrepreneurs and land

investors, and California soon boasted the wealthiest African American community in the country.

California's Black intellectuals built a two-story "Athenaeum"—an educational center complete with 800 books and

a Black museum—and developed a civil rights agenda. In 1855 the new capitol at Sacramento hosted the first of three

annual Black state conventions to demand the right to testify in court, to vote and to have their children educated in public

schools. The Black convention of 1856 created a newspaper, Mirror of the Times to carry news of their successes and protest

campaigns to the state's thirty counties.

California became an early battleground over human rights. In 1846 Mary, a Missouri slave, sued for liberty in a Mexican

court in San Jose and won. During Gold Rush days other enslaved people, often assisted by white attorneys, took their masters

to court or tried to flee to Canada. Slave Biddy Mason reached California the hard way: she walked all the way from Mississippi

in charge of her owner's livestock. Aided by a white Los Angeles sheriff, she served her master with a writ of habeas corpus

and after two days in court was granted liberty for herself and her three daughters. A successful midwife, she invested wisely

in Los Angeles real estate, and became a noted philanthropist.

Of all the western territories only Utah made slavery legal. In 1848 the 1700 Mormons who settled in the Salt Lake Valley

clung to a belief the Scriptures condemned Blacks to servitude. But Mormons and their four dozen enslaved African Americans

began by sharing scarce food, crowded shelters and the cruelties of nature. Two years later Black Mormons were able to hold

assemblies for social and political purposes in their own Salt Lake City building. Though the Mormons promulgated a "slave

code" in 1852 its aim was to discipline masters by requiring them to provide the enslaved decent clothing, food, and opportunities.

It permitted a slave sale only with consent. In 1862 Congress ended slavery in Utah and other western territories.

By then more than a few slaves had freed themselves and headed west. Clara Brown arrived by covered wagon in Denver in

1859 when it was still called Cherry Creek, began a laundry, started the first Sunday school, and used her home to organize

the Saint James Methodist Church. After the Civil War Brown used money she had saved to search for her relatives lost during

slavery. Before she found one daughter, she had brought dozens of former slaves to Colorado and helped them gain an education

and find jobs. In 1885 her funeral was attended by the Governor of Colorado, the Mayor of Denver and conducted by the Colorado

Pioneers Association.

War and emancipation spurred an African American migration to the West. By 1865 Kansas had a Black population of 12,527,

and Leavenworth had two Black churches and 2,400 Black residents. Organized drives for the “sacred right to vote”

were mounted in Kansas, Colorado and Nevada. However, that year Colorado voters rejected an equal suffrage by ten to one,

and the suffrage issue found western Democratic and Republican politicians largely opposed. Congress' Territorial Suffrage

Act of 1867 and the post-war constitutional amendments finally brought the Black suffrage to the West. By 1868 when 120 black

Denver voters provided the margin of victory for the Republican congressional candidate, the party moved toward firmer support

for equality.

Long before they had become free African Americans in the southwest were roping and branding cattle. After the Civil War

they were among 35,000 cowboys who drove Texas cattle up the Chisholm Trail to rail depots in Kansas. In 1925 George Saunders,

president of the Old Time Drivers Association, recalled "about one third of the trail crews were Negroes and Mexicans."

Most cowpunchers were ordinary men such as Nat Love, a former Tennessee slave later known as Deadwood Dick, who honed his

skills on the long drives and worked for $30 a month and grub. Few were as lucky as former slave D.W. Wallace of Texas who

rose from a penniless teen-age cowhand to wealthy ranch owner. Even fewer had the exceptional skills of Bill Pickett.

Called "the greatest sweat and dirt cowhand that ever lived" by Zack Miller, boss of the sprawling 101st Ranch in Oklahoma,

Pickett created the rodeo sport of "bull-dogging” or steer wrestling, one of the seven traditional rodeo contests. Billed

as "The Dusky Demon,” Pickett was star attraction when the 101st rodeo performed in Oklahoma, England, Mexico and at

New York's Madison Square Garden. Pickett's daring finale had him biting into the steer's lip to show his only grip on the

beast was with his teeth.

Most cowhands followed the law but some rode in to break it. In 1877 the Texas wanted list with 5,000 names included every

race. The first man shot in Dodge City was a Black cowhand named Tex, an innocent bystander to a gun duel between two whites.

The first man thrown into Abeline's new stone prison was not innocent and he was black, but his black and white trail crew

shot up the town and rescued him. Black desperadoes such as Cherokee Bill and the Rufus Buck gang of the Oklahoma Territory

were cut in the mold of Billy the Kid and the Dalton gang: they killed without regard to race, color or creed, and paid with

their lives.

Some Black men carried a lawman's badge. Dozens of Black deputies served under "Hanging Judge" Isaac Parker. One, Bass

Reeves, became a legend in his time. In 32 years he shot 14 men, but largely relied on his disguises, detective skills and

knowledge of Indian languages and customs to outwit and arrest dozens of criminals. In 1874 Willie Kennard convinced a skeptical

mayor of Yankee Hill, Colorado to hire him as marshall be facing down Casewit, a deranged killer and rapist, shooting the

two guns from his hands and marching him to jail.

Law and order rode into the western territories with the U.S. Cavalry, which included the Black Ninth and Tenth Regiments,

a fifth of the U.S. Cavalry soldiers in the West, and the 24th and 25th U.S. Infantry Regiments. Native Americans called them

"Buffalo Soldiers" after an animal they relied on for food, clothing and shelter. The Buffalo Soldiers patrolled from the

Rio Grande to the Canadian border, from the Mississippi to the Rockies, and won the respect of every military friend and foe

they encountered. For acts beyond the call of duty more than a dozen Black troopers earned the Congressional Medal of Honor.

However, in Texas they faced harassment and assault from the townspeople they defended.

Rarely did African American women head west alone, but in1868 Elvira Conley arrived in Sheridan, Kansas, a raucous railroad

town ruled by vigilantes. She began a laundry and wisely made friends with two of her best customers, Wild Bill Hickok and

Buffalo Bill. In Sheridan she also met the wealthy Sellar-Bullard merchant family and spent more than half a century serving

as a governess to generations of their children.

The first major Black migration from the southern states began in 1879 when an estimated 8,000 African American men, women

and children who agreed “It is better to starve to death in Kansas than be shot and killed in the South” headed

west. Founded in 1877, Nicodemus, Kansas served as a beacon, especially after Mrs. Francis Fletcher began a one-room school

for 15 Black boys and girls with donated books and a curriculum of literature, hygiene, moral values and mathematics. Mobilized

largely by women, often widows of men slain by white marauders in the deep South, they saw Kansas as a promised land of safety,

education, farms and decent work.

Like the European immigrants who poured into the United States at this time, Black pioneers largely rejected rural life—which

they associated with slavery—for town jobs. Black women pioneers were largely in their 20s to 40s, older and more likely

to be married than white women, and had a lower child-bearing rate than either white women or Black women in the East. They

were five times as likely to have jobs (usually as domestic servants) as white women and twice as likely to be employed as

Indian women.

Celebrating Black History Month 2006 Celebrating Black History Month 2006

The Black West

In 1889 another

great land rush to Oklahoma attracted ten thousand of people of color. Most came from the Deep South and fled mounting violence

hoping to see their women and children protected, gain an education and other opportunities. Leaving home in kinship and friendship

caravans of a hundred or more people, this travel arrangement provided women a protective, comforting blanket. Since these

large caravans included many skilled artisans, the early days of settlement was smoother for Black towns than for white towns.

Residents did not have to solicit or wait for missing artisans, as did white communities. The simultaneous arrival of so many

families and friends also insured cooperation, minimized conflict and spurred town growth and spirit.

The political career of Edwin P. McCabe charts the ebb and flow of power brought by the Black migrations. In the 1880s,

at the height of the Black migration to Kansas, Republicans twice nominated and elected McCabe state auditor, only to denied

him a third term. In 1890 he arrived in Oklahoma, helped found Langston City the next year, and championed Oklahoma as a Black

refuge from racist violence. He planned to settle a black majority in each congressional district and set his eyes on Oklahoma's

territorial governorship. Within eight years Langston City boasted a public school, later a college, and within a decade had

virtually eliminated illiteracy among its 15 to 45 year old men (5%) and women (6%).

Boley, Oklahoma, formed in 1904 on land owned by Abigail Barnett, a Black Indian, in two years had a school with two teachers,

and later a high school that sent half of its graduates to college. In 1908 Booker T. Washington called Boley "striking evidence"

of "land-seekers and home-builders . . . prepared to build up the country." By World War I a thousand Black people lived in

Boley, and two thousand ran nearby farms.

Between 1890 and 1910 32 all-Black towns sprouted in Oklahoma. Men ran the governments but women organized community events,

built schools, churches and self-help societies and planted middle class values. Then, in 1907 Oklahoma entered the Union

as another white supremacy state, the first to segregate telephone booths. Blacks towns still elected local officials but

not national or state officers, and Oklahoma fell under the bigoted hand of the state's justice system. Segregation laws and

declining agricultural prices spelled ruin, and most Black towns became ghost towns. McCabe's political goal sputtered to

earth and he left for Chicago where in 1920 he died in poverty. But his dream lived on in Black migrants' resounding victories

over illiteracy.

Women remained a major staple of Black community strength. They put up the walls and nailed down the floors of frontier

schools, churches, and self-help societies. In 1864 women in Virginia City, Nevada began the First Baptist Church with a new

bound Bible and a dozen hymnbooks. These pioneers went on to demand public education for their children, to begin literary

societies, and in 1874 held a Calico Ball for the 374 Blacks living largely in western Nevada.

In Montana, in 1888 Black women started a St. James Church and the next year a Methodist Episcopal Church. By 1924 31 delegates

assembled in Bozeman as representatives of Montana's Federation of Black Women's Clubs. In Denver, Colorado in 1906 the Colored

Women's Republican Club proudly reported a larger percentage of Black women voted in the city election than white women. By

1910, and largely due to the efforts of women, illiteracy among African Americans in California, Oregon and the Mountain States

had been reduced to less than 10%. Even in western prisons 87% of Black women inmates could read and write.

In many locales Black women were so rare that Black bachelors would meet incoming stagecoaches and trains seeking a marriage

partner. Western women were far more likely to marry than their sisters in the east. In Arizona mining towns it was married

Black women who, distressed by the single men who disturbed the peace at night and on weekends, formed the “Busy Bee

Club.” Their strategy was to contact Black churches and newspapers in the east and arrange for the transportation of

mail order brides-to-be for unmarried miners. Young women, promising to wed the men who paid their fare, boarded trains for

Arizona. Young brides survived tense wedding days to meet the challenges of frontier family life.

Other Black towns sprouted. California gave birth to Albia, Allensworth, Bowles, Victorville, and Texas produced Andy,

Booker, Board House, Cologne, Independence Heights, Kendleton, Oldham, Mill City, Roberts, Shankleville and Union City. The

last high plains Black settlement was Dearfield, Colorado, founded in 1910 by Oliver and Minerva Jackson and settled by 700

poor, older women and men with little capital and scant farming experience. During World War I Dearfield prospered only to

be struck by water shortage and searing winds and finally toppled by the post-war agricultural depression.

Black farming communities had marched into battle without the necessary weapons. Black pioneers, having less capital than

whites, were unable to purchase the large acreage required for survival. Unable to get easy credit, they became less able

to weather economic and natural disasters. And like rural whites, in the age of the automobile and movies, the jobs and bright

lights of cities constantly lured their young.

The West produced unusual and distinguished women and men of color. In 1866 Cathy Williams dressed as "William Cathy" and

served for two years as a soldier in the Buffalo Soldiers. Barney Ford built a palatial Inter-Ocean Hotel in Denver and then

another in Cheyenne, Wyoming. An African American cowpuncher named Williams taught a New York City tenderfoot named Theodore

Roosevelt how to break in a horse, and another Black cowboy named Clay taught movie star Will Rogers his first rope tricks.

Mifflin Gibbs rose from a California bootblack to start the state's first Black newspaper, graduated college and became a

judge in Little Rock, Arkansas.

In Texas, Sutton Griggs at 26 became a Baptist minister and a published novelist, and went on to write seven books of fiction

and essays. Born a slave in Texas, Lucy Gonzales Parsons became the first prominent socialist revolutionary of color, an advocate

for the wretched of the earth and a voice for the working class in the United States. As editors of the popular Seattle Republican,

Susan and Horace Cayton became wealthy and leading citizens of the new state of Washington. Six foot, 200 pound Mary Fields

ran a restaurant and laundry in Cascade, Montana, and in her sixties as "Stagecoach Mary" delivered the U.S. Mail and drove

a stagecoach. In 1898 widow May Mason of Seattle rushed off to the Yukon, Alaska gold rush and returned with $5,000 in gold

and a $6,000 land claim. Oscar Micheaux wrote seven novels, including two fictionalized autobiographies of his life in South

Dakota, and as a pioneer movie producer wrote 45 films that cast his people as cowboys, detectives and doctors.

African American pioneers were a hearty breed and they had to be, for they faced more than their white counterparts. To

live at peace on the frontier, they had to survive the raging storms of nature and man, and overcome the bony hand of bigotry. Like

the other pioneers, African Americans strode across the broad plains and mountains seeking their dream, and some found it

by dint of hard work and luck. But their sojourn often was a frontier experience with a difference. Their families needed

a place where skill would count more than skin color, where women and children would find safety, education and a chance in

the race for life, and where men would find decent jobs. Most Black pioneers sought to avoid the genocidal bigotry and murderous

land-hunger that stained European trails into the wilderness, and tried to be good neighbors on all sides.

With undaunted spirit, raw courage and a dogged persistence, Black pioneers added a new dimension to western life. They

more than earned a right to ride off into the sunset and across the pages of history books.

|

|

| BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

MACDUFF EVERTON / CORBIS |

| “History changes

things,” says author Cornelia Walker Bailey, (above) who lives on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Her surname

started out as Bilali, the given name of her ancestor Bilali Mohammed. Trained as a Muslim prayer leader in his native Guinea,

he was enslaved in 1803 and brought to Sapelo Island, where a small community of his descendants still lives. Bailey grew

up saying Christian prayers facing east, the direction of Makkah—the same direction in which her Muslim ancestor prayed.

Above Left : W. C. Handy, “Father of the Blues” and a son of former slaves, recorded a 1903 encounter

with a man playing an instrument that was evolving from an African zither into an American slide guitar. |

Written by Jonathan Curiel

ylviane Diouf knows her audience might be skeptical, so to demonstrate the connec- tion between Muslim traditions and American

blues music, she’ll play two recordings: The athaan, the Muslim call to prayer that’s heard from minarets

around the world, and “Levee Camp Holler,” an early type of blues song that first sprang up in the Mississippi

Delta more than 100 years ago. ylviane Diouf knows her audience might be skeptical, so to demonstrate the connec- tion between Muslim traditions and American

blues music, she’ll play two recordings: The athaan, the Muslim call to prayer that’s heard from minarets

around the world, and “Levee Camp Holler,” an early type of blues song that first sprang up in the Mississippi

Delta more than 100 years ago.

“Levee Camp Holler” is no ordinary song. It’s the product of ex-slaves who worked moving earth all day

in post-Civil War America. The version that Diouf uses in presentations has lyrics that, like the call to prayer, speak about

a glorious God. But it’s the song’s melody and note changes that closely resemble oneof Islam’s best-known

refrains. Like the call to prayer, “Levee Camp Holler” emphasizes words that seem to quiver and shake in the reciter’s

vocal chords. Dramatic changes in musical scales punctuate both “Levee Camp Holler” and the adhan. A nasal intonation

is evident in both.

|

|

|

ALAN LOMAX COLLECTION / SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION / "PRISON SONGS", VOL. 1, TRACK 11, ROUNDER RECORDS |

“I did a talk a few years ago at Harvard where I played those two things, and the room absolutely exploded in clapping,

because [the connection] was obvious,” says Diouf, an author and scholar who is also a researcher at New York’s

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. “People were saying, ‘Wow. That’s really audible. It’s

really there.’” It’s really there thanks to all the Muslim slaves from West Africa who were taken by force

to the United States for three centuries, from the 1600’s to the mid-1800’s. Upward of 30 percent of the African

slaves in the United States were Muslim, and an untold number of them spoke and wrote Arabic, historians say now. Despite

being pressured by slave owners to adopt Christianity and give up their old ways, many of these slaves continued to practice

their religion and customs, or otherwise melded traditions from Africa into their new environment in the antebellum South.

Forced to do menial, backbreaking work on plantations, for example, they still managed, throughout their days, to voice a

belief in God and the revelation of the Qur’an. These slaves’ practices eventually evolved—decades and decades

later, parallel with different singing traditions from Africa—into the shouts and hollers that begat blues music, Diouf

and other historians believe.

|

| JOHN GABRIEL STEDMAN, NARRATIVE… (LONDON, 1796) / THE MARINER’S

MUSEUM |

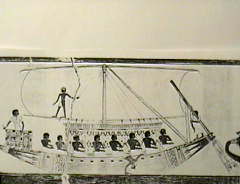

| African Muslim slaves influenced later blues both through their musical style and

through their instruments, which, in late-18th-century Suriname, included percussion, wind and string devices. Among the latter

were a one-string benta (top left), and a Creole-bania (top right), an ancestor of the American banjo. |

Another way that Muslim slaves had an indirect influence on blues music is the instruments they played. Drumming, which

was common among slaves from the Congo and other non-Muslim regions of Africa, was banned by white slave owners, who felt

threatened by its ability to let slaves communicate with each other and by the way it inspired large gatherings of slaves.

Stringed instruments, however—favored by slaves from Muslim regions of Africa, where there’s a long tradition

of musical storytelling—were generally allowed because slave owners considered them akin to European instruments such

as the violin. So slaves who managed to cobble togethera banjo or other instrument—the American banjo originated with

African slaves—could play more widely in public. This solo-oriented slave music featured elements of an Arabic–Muslim

song style that had been imprinted by centuries of Islam’s presence in West Africa, says Gerhard Kubik, a professor

of ethnomusicology at the University of Mainz in Germany. Kubik has written the most comprehensive book on Africa’s

connection to blues music, Africa and the Blues (1999, University Press of Mississippi).

Kubik believes that many of today’s blues singers unconsciously echo these Arabic–Muslim patterns in their

music. Using academic language to describe this habit, Kubik writes in Africa and the Blues that “the vocal

style of many blues singers using melisma, wavy intonation, and so forth is a heritage of that large region of West Africa

that had been in contact with the Arabic–Islamic world of the Maghreb since the seventh and eighth centuries.”

(Melisma is the use of many notes in one syllable; wavy intonation refers to a series of notes that veer from major to minor

scale and back again, something that’s common in both blues music and in the Muslim call to prayer as well as recitation

of the Qur’an. The Maghreb is the Arab–Muslim region of North Africa.)

Kubik summarizes his thesis this way: “Many traits that have been considered unusual, strange and difficult to interpret

by earlier blues researchers can now be better understood as a thoroughly processed and transformed Arabic–Islamic stylistic

component.”

The extent of this link between Muslim culture and American blues music is still being debated. Some scholars insist there

is no connection, and many of today’s best-known blues musicians would say their music has little to do with Muslim

culture. Yet a growing body of evidence—gathered by academics such as Kubik and by others such as Cornelia Walker Bailey,

a Georgia author whose great-great-great-great-grandfather was a slave who prayed toward Makkah—suggests a deep relationship

between slaves of Islamic descent and us culture. While Muslim slaves from West Africa were just one factor in the formation

of American blues music, they were a factor, says Barry Danielian, a trumpeter who’s performed with Paul Simon,

Natalie Cole and Tower of Power.

Danielian, who is Muslim, says non-Muslims find this connection hard to believe because they don’t know enough about

Arabic or Muslim music. The call to prayer and other Muslim recitations that were practiced by American slaves had a musicality

to them, just as these recitations still do, even if they aren’t thought of as music by westerners, Danielian says.

|

| E. DEN OTTER / KIT TROPENMUSEUM |

|

Above: The largest of the banjo ancestors is the kora of the Mandinka people in today’s Senegal,

Guinea-Conakry and Gambia. It traditionally uses 21 strings and a large calabash-gourd body.

Below: The West African lute known as the ngoni is played in the “clawhammer style” formerly

popular for playing today’s banjos. For almost every note of the scale, there is a different tuning for the ngoni and

a different pattern of playing. |

|

| ROBERT C. NEWTON |

“In my congregation,” says Danielian, who lives in Jersey City, New Jersey, “when we get together, especially

when the shaykhs [leaders] come and there are hundredsof people and we do the litanies, they’re very musical. You hearwhat

we as Americans would call soulfulness or blues. That’s definitely in there.”

What people now think of as blues music developed in the 1890’s and early 1900’s, in southern us states such

as Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. Blues music was an outgrowth of all the different music that was then being performed

in the South, from minstrels to street shows. Early blues performers didn’t recognize the music’s African or Muslim

roots because, by then, the songs had more fully merged with white, European music and had lost their obvious connections

to a continent that was 4000 miles away. Also, by the turn of the 20th century, the progeny of America’s Muslim slaves

had generally converted to Christianity, either by force or circumstance. Among southern blacks in that period, there were

few exponents of Islam. But as more scholars research that period in history, they see plenty of signs that weren’t

obvious 100 years ago.

Take the case of W. C. Handy, who earned the moniker “Father of the Blues” for the way he formalized blues

music over a 40-year career of writing songs and playing the cornet. In his autobiography, Handy, whose parents were slaves,

writes about a life-changing moment that happened to him around 1903. Handy was sleeping at a train station in Tutwiler, Mississippi

when “a lean, loose-jointed Negro had commenced plucking a guitar beside me while I slept. His clothes were rags; his

feet peeped out of his shoes. His face had on it some of the sadness of the ages. As he played, he pressed a knife on the

strings of the guitar…. The effect was unforgettable. His song, too, struck me instantly.... The singer repeated the

line (“Goin’ where the Southern cross’ the Dog”) three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with

the weirdest music I had ever heard.”

The song was about a nearby train station where different train lines intersected. As Handy noted in the autobiography,

published in 1941, “Southern Negroes sang about everything. Trains. Steamboats, steam whistles, sledgehammers, fast

women, mean bosses, stubborn mules—all became subjects for their songs. They accompany themselves on anything from which

they can extract a musical sound or rhythmical effect, anything from a harmonica to a washboard. In this way, and from these

materials, they set the mood for what we now callthe blues.”

While washboards, in fact, became popular among later blues musicians such as Robert Brown (known as “Washboard Sam”),

the technique that Handy witnessed—that of pressing the back of a knife blade on guitar strings—can be traced

to Central and West Africa, where, as Kubik points out in Africa and the Blues, people play one-string zithers that

way. Handy assumed that the technique, now called “slide guitar,” was borrowed from Hawaiian guitar playing, but

it’s more likely that the itinerant guitar player that Handy met in Tutwiler was manifesting his African roots. Kubik

has traveled to Africa many times for his research and has lived there. While washboards, in fact, became popular among later blues musicians such as Robert Brown (known as “Washboard Sam”),

the technique that Handy witnessed—that of pressing the back of a knife blade on guitar strings—can be traced

to Central and West Africa, where, as Kubik points out in Africa and the Blues, people play one-string zithers that

way. Handy assumed that the technique, now called “slide guitar,” was borrowed from Hawaiian guitar playing, but

it’s more likely that the itinerant guitar player that Handy met in Tutwiler was manifesting his African roots. Kubik

has traveled to Africa many times for his research and has lived there.

Bailey, who visited West Africa in 1989, says the African and Muslim roots of southern us traditionsare often mistaken

for something else.

Bailey lives on Georgia’s Sapelo Island, where some blacks can trace their ancestry to Bilali Mohammed, a Muslim

slave who was born and raised in what is now the African nation of Guinea. Visitors to Sapelo Island are always struck by

the fact that churches there face east. In fact, as a child, Bailey learned to say her prayers facing east—the same

direction that her great-great-great-great-grandfather faced when he prayed toward Makkah.

Bilali was an educated man. He spoke and wrote Arabic, carried a Qur’an and a prayer rug, and wore a fez that likely

signified his religious devotion. Bilali had been trained in Africa to be a Muslim leader; on Sapelo Island, he was appointed

by his slave master to be an overseer of other slaves. Although Bilali’s descendents adopted Christianity, they incorporated

Muslim traditions that are still evident today.

|

| COURTESY BARRY DANIELIAN / BDEEP MUSIC |

|

To trumpeter Barry Danielian, Muslim prayers are “very musical. You hear what we as Americans would call soulfulness

or blues. That’s definitely in there.” |

The name Bailey, in fact, is a reworking of the name Bilali, which became a popular Muslim name in Africa because one of

Islam’s first converts—and the religion’s first muezzin—was a former Abyssinian slave named Bilal.

(Muezzins are those who call Muslims to prayer.) One historian believes that abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who changed

his name from Frederick Bailey, may also have had Muslim roots.

“History changes things,” says Bailey, who chronicled the history of Sapelo Island in her memoir God, Dr.

Buzzard, and the Bolito Man (2001, Anchor). “Things become something different from what they started out as.”

A good example is the song “Little Sally Walker.” It’s been recorded by many blues artists, but it’s

also been recorded as “Little Sally Saucer” because the lyrics describe a girl “sittin’ in a saucer.”

Frankie Quimby, a relative of Bailey’s who also traces her roots to Bilali Mohammed, says the song originated during

slavery on the Georgia coast, written by songwriting slaves who took their slaveholder’s last name, Walker, as their

own. “I’ve seen [people] take the song and use different words,” says Quimby, who sings slave songs with

her husband in a group called the Georgia Sea Island Singers.

Because there is little documentation about these slave-time origins, it’s easy to argue about what can be unequivocally

linked to Africa and Muslim culture. Muslim and Arab culture have certainly been influences on other music around the world,

including flamenco, which is rooted in seven centuries of Muslim rule in Spain, and Renaissance music. So far, knowledge of

Muslim culture’s association with blues music seems limited to a select group of academics and musicians. Books such

as Kubik’s Africa and the Blues and Diouf’s Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas

(1998, New York University Press) are more geared toward university audiences.

In terms of popular culture, it’s hard to find a single work—whether it’s a novel, movie, song or other

art form—that covers the intersection of Muslim culture, music and African slaves. “Daughters of the Dust,”

Julie Dash’s 1991 film about life on the Sea Islands of Georgia, features a Muslim man who portrays Bilali Mohammed,

but a scene that shows him in prayer lasts just a few moments, and the movie received limited release.

Roots, Alex Haley’s novel that was made into ahistoric television series in the 1970’s, featured a

main character (Kunte Kinte) who is Muslim, although novelist James Michener and others doubted the authenticity of Haley’s

work.

The trading of African slaves led to a diaspora unlike any other in human history, with at least 10 million Africans bought

and sold into bondage in the Americas. The pain felt by those slaves is evident in American blues music—a music that’s

often about cruel treatment, sad times and a yearning to break free. Blues music is a unique American art form that went around

the world and, in turn, influenced history. Without the blues, there wouldn’t be jazz and there wouldn’t be the

bluesy music of the Rolling Stones and the Beatles.

|

| RAYMOND GEHMAN / CORBIS |

|

In the Memphis city park that carries his name, a statue of W. C. Handy commemorates his introduction of the blues along

the city’s famously musical Beale Street. |

In his book Black Music of Two Worlds (1998, Schirmer), author John Storm Roberts says he can hear patterns of

African Muslim music in the songs of Billie Holiday. Roberts refers to the “bending of notes” that is evident

in Holiday’s sad, soulful ballads, as it is in the call to prayer. This same note-bending can be heard in the music

of B. B. King and John Lee Hooker.

Blues music, with its strong tempos and many lyrical references to relationships, has been described as “the devil’s

music” by those outside it. Many conservative Muslims think of blues music as decadent and indicative of permissive

western morals. But people such as Diouf, Kubik and Moustafa Bayoumi, an associate professor of English at Brooklyn College,

City University of New York, who has researched Muslim culture’s connection to American music, are trying to correct

the public record. Bayoumi wrote a paper several years ago that examined African Muslim history in the United States. In it,

he argues that John Coltrane’s best-known album, “A Love Supreme,” features Coltrane saying, “Allah

supreme” in addition to the many refrains of“a love supreme.”

“It’s about uncovering a hidden past,” says Bayoumi, asked about the spate of new scholarship on the

subject of Islam and African–Americans. “You can hear [influences of Muslim culture] in even the earliest days

of American blues music. What you’ve gotten lately is an ethnomusicology that’s trying to reconstruct that. These

are deliberate attempts to rebuild a bridge, as it were.”

|

|

|

|

|

Christianity AnD Africa

Christianity first arrived in North Africa, in the 1st or early 2nd century AD. The Christian communities in North Africa

were among the earliest in the world. Legend has it that Christianity was brought from Jerusalem to Alexandria on the Egyptian

coast by Mark, one of the four evangelists, in 60 AD. This was around the same time or possibly before Christianity spread

to Northern Europe. Once in North Africa, Christianity spread slowly West from Alexandria and East to Ethiopia. Through

North Africa, Christianity was embraced as the religion of dissent against the expanding Roman Empire. In the 4th century

AD the Ethiopian King Ezana made Christianity the kingdom's official religion. In 312 Emperor Constantine made Christianity

the official religion of the Roman Empire.  In the 7th century Christianity retreated under the advance of Islam. But it remained the chosen religion of the

Ethiopian Empire and persisted in pockets in North Africa. In the 15th century Christianity came to Sub-Saharan Africa

with the arrival of the Portuguese. In the South of the continent the Dutch founded the beginnings of the Dutch Reform Church

in 1652. In the interior of the continent most people continued to practice their own religions undisturbed until

the 19th century. At that time, Christian missions to Africa increased, driven by an antislavery crusade and the interest

of Europeans in colonising Africa. However, where people had already converted to Islam, Christianity had little success.

Christianity was an agent of great change in Africa. It destabilised the status quo, bringing new opportunities to

some, and undermining the power of others. With the Christian missions came education, literacy and hope for the disadvantaged.

However, the spread of Christianity paved the way for commercial speculators, and, in its original rigid European form, denied

people pride in their culture and ceremonies.

August 2000

Legacy Stolen

Black people In Amerikkka, we need to

start researching "our" history. And stop settling for the European lies--in books that are provided to you in high school

and college. So much can open up to you... once you take the time to do research. The science of Philosophy was stolen from

Ancient Kemet (Land of the Black), Egypt is what the greeks changed it to after they invaded. From 2700 to 1290 B.C., the

Egyptians were the light of the ancient world. They produced many early medical instruments, designed the world's first step

pyramid, and laid the empirical groundwork for scientific reasoning. Below is the research that I did on the subject of Northern

Afrika. Black people In Amerikkka, we need to

start researching "our" history. And stop settling for the European lies--in books that are provided to you in high school

and college. So much can open up to you... once you take the time to do research. The science of Philosophy was stolen from

Ancient Kemet (Land of the Black), Egypt is what the greeks changed it to after they invaded. From 2700 to 1290 B.C., the

Egyptians were the light of the ancient world. They produced many early medical instruments, designed the world's first step

pyramid, and laid the empirical groundwork for scientific reasoning. Below is the research that I did on the subject of Northern

Afrika.

Suppose you walked out of your front door and looked up into

the sky and instead of seeing the stars as separate entities, you saw them connected to each other by some visible linkage.

To understand the African way of thinking it is necessary to suspend for a while linearity, and to consider the entire world,

even the universe and universes, as one large system where everything’s connected and interconnected. This is the principle

African way of equality (Asante 1990). Because of a legacy of denigration that portrays Africa as incapable of abstract thought,

the question “What is African philosophy?” is often the first that occurs to those outside the field. This legacy

is reinforced by the assumption that philosophy requires a tradition of written communication that is foreign to Africa (Samuel

1980). The African conception of reality is often difficult for those educated in the west, or influenced by the West, where

the notion of reality is so mired in empiricism dependant solely upon the operation of the senses. Africa’s influence

on ancient Greece, the oldest European civilization, was profound and significant in art, architecture, astronomy, medicine,

geometry, mathematics, law, politics, and religion. Yet there has been a furious campaign to discredit African influence and

to claim a miraculous birth for Western civilization. My assessment is to try and prove that Greeks were not the founders

of philosophy, but the people of North Africa commonly known as Egyptians were.

As one attempts to read the history of

Greek philosophy, you will discover a complete absence of essential information concerning the early life and training of

the so-called Greek philosophers, from Thales to Aristotle (James 2001). No writer or historian professes to know anything

about their early education. All they tell us about them consists of doubtful dates and places of birth. The world is left

to ponder who they were and what sources chartered there early education, and would naturally expect that men who rose to

the position of a teacher among relatives, friends and associates, would be well-known, not by them, but by the entire community.

Teachers in history who have taught others are represented as unknown, being without any domestic, social or early educational

traces. This is unbelievable, and yet it is a fact that history of Greek philosophy has presented to the world a number of

men whose lives we know little or nothing about, but expects the world to accept them as true authors of the doctrines which

are alleged to be theirs (James 2001). In the absence of essential evidence, the world hesitates to recognize them as such,

because the truth of this whole matter of Greek philosophy points in a very different direction. Namely, a direction found

in North Africa.

The

astronomers, physicists and mathematicians of ancient Greece were innovators or just very good copycats. Ancient Greeks used

letters and extra symbols to represent digits. But one thing it seems the ancient Greeks did not invent was the counting system

on which many of their greatest thinkers based their pioneering calculations. New research suggests the Greeks borrowed their

system known as alphabetic numerals from the Egyptians, and did not develop it themselves as was long believed. Greek alphabetic

numerals were favored by the mathematician and physicist Archimedes, the scientific philosopher Aristotle and the mathematician

Euclid, amongst others. There are striking similarities between Greek alphabetic numerals and Egyptian demotic numerals, used

in Egypt from the late 8th Century BC until around AD 450 (Aaboe 1964). Both systems use nine signs in each base so that individual

units are counted 1-9; tens are counted 10-90 and so on. Both systems also lack a symbol for zero. Egyptians used hieratic

and, later, demotic script where the multiple symbols looked more like single symbols. Instead of seven vertical strokes,

a particular squiggle was used. That’s the same scheme used in the Greek alphabetic numerals. Explosion in trade between

Greece and Egypt after 600 BC led to the system being adopted by the Greeks (Aaboe 1964). Greek merchants may have seen the

demotic system in use in Egypt and adapted it for their own purposes.

In his magnum opus A Lost Tradition:

African Philosophy in World History (1975), Thoephile Obenga documents the confessions of ‘famous’ revered Greeks

(the world’s first Europeans) in their own Greek Hellenic language that they all received their education at the Temple

of Waset in ancient Kemet (Egypt) and that their teachers were the master-thinkers or High priests in the Nile Valley.

The Temple of Waset is the world’s

first university and was built during the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep 111 in the XV111 Dynasty, 1405-1370 B.C. For example,

“it is generally taught that Thales of Miletus (624-547 B.C.) was the first Greek philosopher and the founder of the

Presocratic Ionian school in Asia Minor (and) is traditionally the first (protos) to have revealed the investigation of nature”.

The truism is that Thales “received his training from Egyptian priests in the Nile Valley. This is clearly recorded

by the Greeks themselves. “According to “corpus of Greek testimonia with regard to the fruitful instruction received

by Thales in Egypt: “Thales, one of the so called ‘Seven Sages’, had no regular teacher in his life save

for the priests of Egypt, under whom he studied.” (pg. 28).

“Thales of Miletus had never been

taught by a master in Greece. Thales’ pursuit of instruction saw him go by sea to Egypt, where he spent time with the

Egyptian priests.” Plato records that Thales was educated in Egypt under the priests: “Thales was well and truly

indebted to Egypt for his education.” According to Aetius, “Thales studied philosophy in Egypt for a long enough

period to be considered an elder when he returned.”(p.29). “The science of geometry was invented in Egypt. Thales

transferred the speculative science of geometry to Greece. There was no method of intellectual inquiry such as geometry in

Greece before Thales’ departure for Egypt.

Upon his return, however, Thales introduced

geometry (geometrein) in Greece.” (p.31). Indeed, “more than 1,000 years before Thales’ birth, Egyptians

had correctly calculated the areas of rectangles, triangles and isosceles trapeziums. The area of a circle had also been obtained

accurately.” (p.32). The Greek Hellenic record shows that Pythagoras (born circa 572 B.C.) like another ancient philosopher

(he) Pythagoras journeyed in his youth to Egypt where, for an indefinite number of years, he pursued studies in astronomy,

geometry, and theology under the tutelage of Egyptian priests.”(p.34). It was Thales who “had recommended that

above all, Pythagoras should meet the clergy of Memphis and Thebes (old capitals of Kemet) in order to gain a higher level

of knowledge.” (p.37)

Plato

also copied/derived his so-called four virtues: wisdom, justice, courage and temperance from the original Egyptian spiritual

belief system which contained ten virtues. (p.8). The Greeks re-named this belief system the Mystery System. In his Nile Valley

Contribution to Civilizations (1992), Anthony T. Browder points out that “Homer, the Greek poet, praised the glory of

this great (Egyptian) city (“Thebes”) in The Illiad (circa 750 B.C.)” and “Rome’s classical

literature of religious and moral teachings” was written in 1 B.C. by poet Virgil. This “great work””

called the Aeneid consisted of 12 books “Virgil based the first six books on the Odyssey and the last six books were

modeled after the Illiad.” The truism is that “Virgil wrote the Aeneid to establish the divinity of the Roman

empire, which he closely associated with that of Greece” which in turn, was closely associated with and derived from,

the original Kemetic ennead of Gods and Goddesses as follows (p.169).

Now, while the Africans/Kemites were writing these medical

texts and performing all these medical operations, the Greek Hypocrates, was not born yet, until 333 B.C. almost 2,000 years

after the African originality in medicine. Imhotep, the world’s “first recorded multi-genius” is regarded

as the real Father of Medicine. He was born in 2800 B.C. So instead of taking the derived European-Greek Hypocratic Oath,

(which contains two African/Kemetic Gods Heru and Imhotep), medical students today should take the true, original Imhotep

Oath. Hypocrates only spent 20 years studying medicine at the Temple of Waset (renamed Thebes by the Greeks and Luxor by the

Arabs). As such, he is a student/child of medicine, not the ‘Father’. Imhotep also built the Step Pyramid-the

world’s first stone monument-at Saqqara, 111th Dynasty circa 2730 B.C.; this proves that Africans/Kemites invented architecture

– a genre of architecture that was later copied and duplicated in Greece. As a philosopher, Imhotep is credited with

having written the slogan: “Eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow we shall die.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

Predynastic

About 5500-3000 B.C.

Climatic change about 7,000 years ago

turns most of Egypt—except for along the Nile—to desert. Farming begins and communities form along the river,

with important population centers at Buto, Naqada, and Hierakonpolis. Egypt remains divided into Upper and Lower (southern

and northern) Egypt. |

|

|

|

Early Dynastic

(Dynasties I-III)

2950-2575 B.C.

Consolidation of Upper

and Lower Egypt and founding of Memphis, the first capital. Calendar and hieroglyphic writing created. Royal necropolis located

at Abydos; vast cemeteries at Saqqara and other sites.

|

|

Old Kingdom

(Dynasties IV-VIII)

2575-2150 B.C.

Age of pyramids reaches

zenith at Giza; cult of the sun god Re centered at Heliopolis. Cultural flowering; trade with Mediterranean region and brief

occupation of Lower Nubia. |

|

|

|

First Intermediate Period

(Dynasties IX-XI)

2125-1975 B.C.

Political chaos as Egypt

splits into two regions with separate dynasties. |

|

Middle Kingdom

(Dynasties XI-XIV)

1975-1640 B.C.

Reunification by Theban

kings. Dynasty XII kings win control of Lower Nubia; royal burials shift north to near Memphis. Major irrigation projects.

Classical literary period.

|

|

|

|

Second Intermediate Period

(Dynasties XV-XVII)

1630-1520 B.C.

Asiatic Hyksos settlers

rule the north, introducing the horse and chariot; Thebans rule the south.

|

|

New Kingdom

(Dynasties XVIII-XX)

1539-1075 B.C.

Thebans expel the

Hyksos and reunite Egypt. In this "age of empire," warrior kings conquer parts of Syria, Palestine, and Lower Nubia. |

|

|

|

Third Intermediate Period

(Dynasties XXI-XXIV)

1075-715 B.C.

Egypt is once again

divided. The high priests of Amun control Thebes; ethnic Libyans rule elsewhere. |

|

Late Period

(Dynasties XXV-XXX)

715-332 B.C.

Nubians from Kush conquer

Egypt; Egypt reunited under Saite dynasty. Persia rules in fifth century B.C. Egypt independent from 404 to 343 B.C. |

|

|

|

Greco-Roman Period

332 B.C.-A.D. 395

Ptolemies rule after the death of Alexander

the Great in 332 B.C. Dramatic growth of population and agricultural output. Roman emperors build many temples, depicting

themselves in the Egyptian style. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Truth About Columbus

Christopher Columbus, whose real name is Cristobol Colon, of course did not discover America in 1492. In fact, he never

claimed to have done so; white historians did it for him. Indigenous people and Afrikans were already living in the western

hemisphere, thousands of years before his expedition.

Colon never stepped foot on the American mainland. He landed

in the Caribbean islands.

Upon landing there, he received reports of Afrikans having visited there before Colon's

voyages.

In fact, ancient Afrikans had traveled to the western hemisphere at least two thousand years before Colon

was born. Afrikans, (ancient Kemetics (Egyptians)), had also sailed to the Pacific Islands at least 1,000 years before Colon

was born.

Colon praised the hospitality of the Indigenous people, yet said that they had to be destroyed in order

to take control of the wealth of the lands.

Colon came to the western hemisphere by mistake. He was searching for

the "East" looking for, among other things, spices and other commodities to help a starving Europe to preserve their meats.

Since Europeans did not, at that time, have knowledge of longitude and latitude, Colon ended up sailing West to the

Caribbean Islands. Arriving there, he called the Indigenous people "Indians", thinking he was in the Asian country of India.

Thus, he re-named all of the Indigenous people "Indians" which was not their natural names. He later had Afrikan navigators

on board who knew longitude and latitude.

Prior to sailing to the West, Colon sailed along the coast of West Afrika, capturing Afriknas for enslavement in Portugal.

Enslavement of Afrikans and Indigenous people in the West was facilitated by Papal Bulles (bulletins/edicts) issued

by Popes of the Christian Roman Catholic Church. In 1455, the Pope issued a bulle to Portugal that authorized it to reduce

to servitude (enslave) "infidels" (non-christian) people. This was followed by a Papl bulle issued by Pope Innocent VIII in

1491 that divided the world into two halves for the purpose of enslaving Afrikan and Indigenous people. The Pope gave the

eastern half (Afrika, etc.) to Portugal, and the western half (the Americas, ect.) to Spain. Colon came to the Americas representing

Spain. Britain, France, and other enslaving European countries did not follow this protocol and the mad dash to slice up the

world for European benefit began and its damaging effects persist to this day.

The significance of Cristobol Colon's

voyages to the western hemisphere, is that this opened up Afrika and the Americas to mass murder, rape, destruction of entire

cultures, stolen wealth of the people, and mass enslavement of Afrikans and the Indigenous people of the Americas for hundreds

of years by Europeans. European profits from enslavement were upwards of 5000 percent!!

Dr. Cheikh Anta Diop has esteimated

that upwards of 300 MILLION Afrikans lost their lives during the 400+ years of European enslavement.

Many Indigenous

people of the Caribbean Islands were totally destroyed by European enslavement.

It is this mass enslavement that provided

America and Europe with the vast resources of wealth, natural resources, and free labor that enabled them to gain world domination

on the backs of Afrikan and other Indigenous people of the world.

To Afrikans, celebrating Columbus Day is celebrating

the mass destruction of your own people! Columbus Day ought to be a day of mourning, not of celebration.

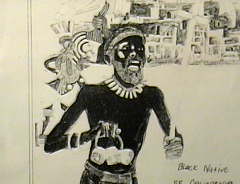

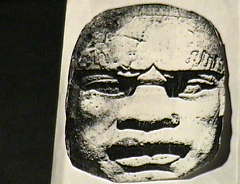

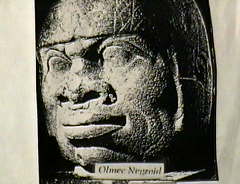

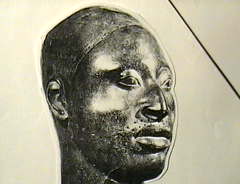

BLACK CIVILIZATIONS OF

ANCIENT AMERICA (MUU-LAN),

MEXICO

(XI)

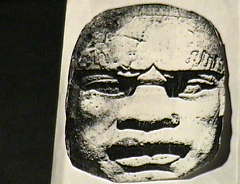

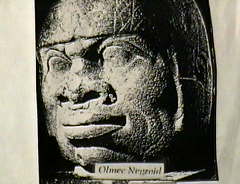

Gigantic stone head of Negritic African

during the Olmec (Xi)

Civilization

By Paul Barton  The earliest people in the Americas were people of the Negritic African

race, who entered the Americas perhaps as early as 100,000 years ago, by way of the bering straight and about thirty thousand

years ago in a worldwide maritime undertaking that included journeys from the then wet and lake filled Sahara towards the

Indian Ocean and the Pacific, and from West Africa across the Atlantic Ocean towards the Americas. According to the Gladwin

Thesis, this ancient journey occurred, particularly about 75,000 years ago and included Black Pygmies, Black Negritic peoples

and Black Australoids similar to the Aboriginal Black people of Australia and parts of Asia, including India. The earliest people in the Americas were people of the Negritic African

race, who entered the Americas perhaps as early as 100,000 years ago, by way of the bering straight and about thirty thousand

years ago in a worldwide maritime undertaking that included journeys from the then wet and lake filled Sahara towards the

Indian Ocean and the Pacific, and from West Africa across the Atlantic Ocean towards the Americas. According to the Gladwin

Thesis, this ancient journey occurred, particularly about 75,000 years ago and included Black Pygmies, Black Negritic peoples

and Black Australoids similar to the Aboriginal Black people of Australia and parts of Asia, including India.

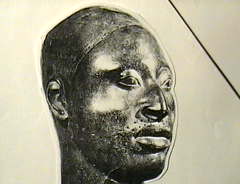

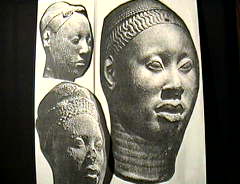

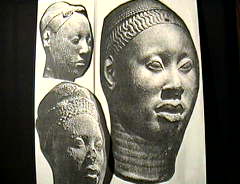

Ancient African terracotta portraits 1000 B.C. to 500 B.C.  Recent discoveries in the

field of linguistics and other methods have shown without a doubt, that the ancient Olmecs of Mexico, known as the Xi People,

came originally from West Africa and were of the Mende African ethnic stock. According to Clyde A. Winters and other writers

(see Clyde A. Winters website), the Mende script was discovered on some of the ancient Olmec monuments of Mexico and were

found to be identical to the very same script used by the Mende people of West Africa. Although the carbon fourteen testing

date for the presence of the Black Olmecs or Xi People is about 1500 B.C., journies to the Mexico and the Southern United

States may have come from West Africa much earlier, particularly around five thousand years before Christ. That conclusion

is based on the finding of an African native cotton that was discovered in North America. It's only possible manner of arriving

where it was found had to have been through human hands. At that period in West African history and even before, civilization

was in full bloom in the Western Sahara in what is today Mauritania. One of Africa's earliest civilizations, the Zingh Empire,

existed and may have lived in what was a lake filled, wet and fertile Sahara, where ships criss-crossed from place to place. Recent discoveries in the

field of linguistics and other methods have shown without a doubt, that the ancient Olmecs of Mexico, known as the Xi People,

came originally from West Africa and were of the Mende African ethnic stock. According to Clyde A. Winters and other writers

(see Clyde A. Winters website), the Mende script was discovered on some of the ancient Olmec monuments of Mexico and were

found to be identical to the very same script used by the Mende people of West Africa. Although the carbon fourteen testing

date for the presence of the Black Olmecs or Xi People is about 1500 B.C., journies to the Mexico and the Southern United

States may have come from West Africa much earlier, particularly around five thousand years before Christ. That conclusion

is based on the finding of an African native cotton that was discovered in North America. It's only possible manner of arriving

where it was found had to have been through human hands. At that period in West African history and even before, civilization

was in full bloom in the Western Sahara in what is today Mauritania. One of Africa's earliest civilizations, the Zingh Empire,

existed and may have lived in what was a lake filled, wet and fertile Sahara, where ships criss-crossed from place to place.

ANCIENT AFRICAN KINGDOMS PRODUCED

OLMEC TYPE

CULTURES

The ancient kingdoms of West Africa which occupied the Coastal forest belt from Cameroon

to Guinea had trading relationships with other Africans dating back to prehistoric times. However, by 1500 B.C., these ancient

kingdoms not only traded along the Ivory Coast, but with the Phoenicians and other peoples. They expanded their trade to the

Americas, where the evidence for an ancient African presence is overwhelming. The kingdoms which came to be known by Arabs

and Europeans during the Middle Ages were already well established when much of Western Europe was still inhabited by Celtic

tribes. By the 5th Century B.C., the Phoenicians were running comercial ships to several West African kingdoms. During that

period, iron had been in use for about one thousand years and terracotta art was being produced at a great level of craftsmanship.

Stone was also being carved with naturalistic perfection and later, bronze was being used to make various tools and instruments,

as well as beautifully naturalistic works of art.

The ancient West African coastal and interior Kingdoms

occupied an area that is now covered with dense vegetation but may have been cleared about three to four thousand years ago.

This includes the regions from the coasts of West Africa to the South, all the way inland to the Sahara. A number of large

kingdoms and empires existed in that area. According to Blisshords Communications, one of the oldest empires and civilizions

on earth existed just north of the coastal regions into what is today Mauritania. It was called the Zingh Empire and was highly

advanced. In fact, they were the first to use the red, black and green African flag and to plant it throughout their territory

all over Africa and the world.

The Zingh Empire existed about fifteen thousand years ago. The only other civilizations

that may have been in existance at that period in history were the Ta-Seti civilization of what became Nubia-Kush and the

mythical Atlantis civilization which may have existed out in the Atlantic, off the coast of West Africa about ten to fifteen

thousand years ago. That leaves the question as to whether there was a relationship between the prehistoric Zingh Empire of

West Africa and the civilization of Atlantis, whether the Zingh Empire was actually Atlantis, or whether Atlantis if it existed

was part of the Zingh empire. Was Atlantis, the highly technologically sophisticated civilization an extension of Black civilization

in the Meso-America and other parts of the Americas?

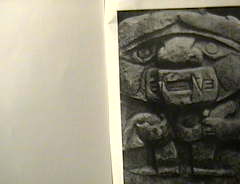

Stone carving of a Shaman or priest

from

Columbia's San Agustine Culture

An ancient West African Oni or King holding similar artifacts as the San Agustine

culture stone carving of a Shaman

The

above ancient stone carvings (500 t0 1000 B.C.) of Shamans of Priest-Kings clearly show distinct similarities in instruments

held and purpose. The realistic carving of an African king or Oni and the stone carving of a shaman from Columbia's San Agustin

Culture indicates diffusion of African religious practices to the Americas. In fact, the region of Columbia and Panama were

among the first places that Blacks were spotted by the first Spanish explorers to the Americas.

|

From the archeological evidence

gathered both in West Africa and Meso-America, there is reason to believe that the African Negritics who founded or influenced

the Olmec civilization came from West Africa. Not only do the collosol Olmec stone heads resemble Black Africans from the

Ghana area, but the ancient religious practices of the Olmec priests was similar to that of the West Africans, which included

shamanism, the study of the Venus complex which was part of the traditions of the Olmecs as well as the Ono and Dogon People

of West Africa. The language connection is of significant importance, since it has been found out through decipherment of

the Olmec script, that the ancient Olmecs spoke the Mende language and wrote in the Mend script, which is still used in parts

of West Africa and the Sahara to this day.

ANCIENT TRADE BETWEEN THE AMERICAS AND AFRICA

The earliest trade and commercial activities between prehistoric and ancient Africa

and the Americas may have occurred from West Africa and may have included shipping and travel across the Atlantic. The history

of West Africa has never been properly researched. Yet, there is ample evidence to show that West Africa of 1500 B.C. was

at a level of civilization approaching that of ancient Egypt and Nubia-Kush. In fact, there were similarities between the

cultures of Nubia and West Africa, even to the very similarities between the smaller scaled hard brick clay burial pyramids

built for West African Kings at Kukia in

pre Christian Ghana and their counterparts in Nubia, Egypt and Meso-America.

Although

West Africa is not commonly known for having a culture of pyramid-building, such a culture existed although pyramids were

created for the burial of kings and were made of hardened brick. This style of pyramid building was closer to what was built

by the Olmecs in Mexico when the first Olmec pyramids were built. In fact, they were not built of stone, but of hardened clay

and compact earth.

Still, even though we don't see pyramids of stone rising above the ground in West Africa, similar

to those of Egypt, Nubia or Mexico, or massive abilisks, collosal monuments and structures of Nubian and Khemitic or Meso-American

civilization. The fact remains, they did exist in West Africa on a smaller scale and were transported to the Americas, where

conditions

such as an environment more hospitable to building and free of detriments such as malaria and the tsetse fly,

made it much easier to build on a grander scale.

|

|

Meso-American pyramid with stepped appearance,

built

about 2500 years ago

Stepped Pyramid of Sakkara, Egypt, built

over

four thousand years ago, compare to Meso-American pyramid

Large scale building projects such as monuent and pyramid building was most likely carried to the Americas

by the same West Africans who developed the Olmec or Xi civilization in Mexico. Such activities would have occurred particularly